In his influential book – “The art of war”, general Sun Tzu wrote, ” If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the results of hundred battles.”

In this article, I will shed light on one of the biggest enemies of all allergy sufferers – pollen.

If you know pollen and its nature, you will be able to take effective measures to reduce allergic symptoms when the pollen is present in the air.

Just as importantly, you will also be able to eliminate medicinal intake when the pollen is absent.

In effect, you will be able to minimize both the allergy symptoms as well as the side effects of the medicine.

Before we dive into the details, just a quick note on the writing style. I will be using the word “plant” as a catch-all to represent trees, shrubs, bushes, grass, and weeds.

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the results of a hundred battles.

Sun TZU – The art of war

What is pollen?

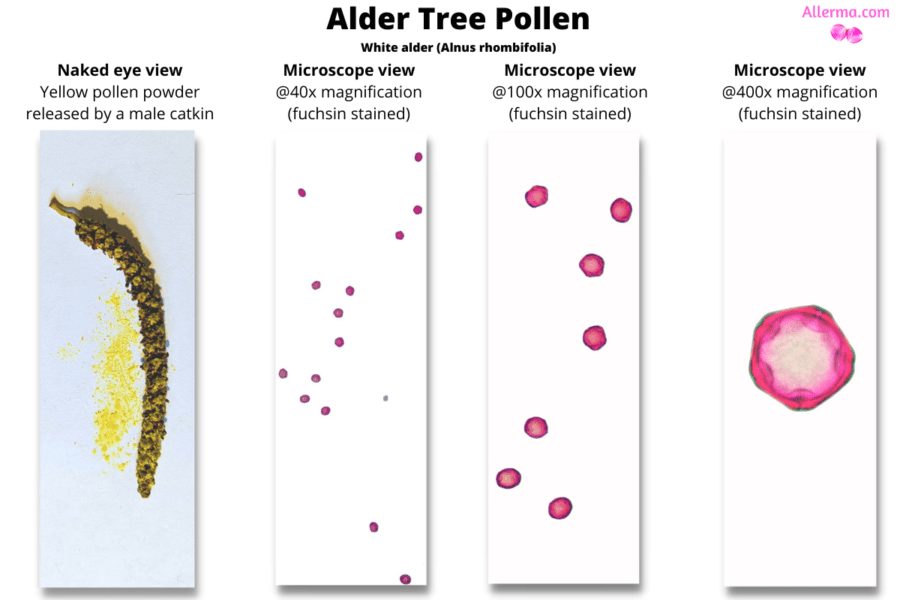

Pollen is a microscopic grain produced by the male part (stamen) of a flower. It plays an essential part in plant reproduction and carries within it the male reproductive cells. Each plant, especially the allergenic type, is capable of producing millions, even billions of pollen each year.

A single grain of pollen is invisible to the naked eye and generally ranges from 5 microns to 100 microns in size (1 micron (µ) = 0.001 mm).

However, collectively thousands of pollen grains are visible as a fine powder. This powder is generally yellow in color for airborne allergenic pollen.

If you ever notice a thin layer of yellow dust on your car, patio, or sidewalk, it probably is pollen shed by a nearby tree.

Plant reproduction relies on pollen to deliver the male reproductive cells to a compatible female’s stigma. However, only a tiny fraction of pollen finds its way to the female counterpart for fertilization. The vast majority just finds its way into the soil, water, or our noses.

How does pollen spread?

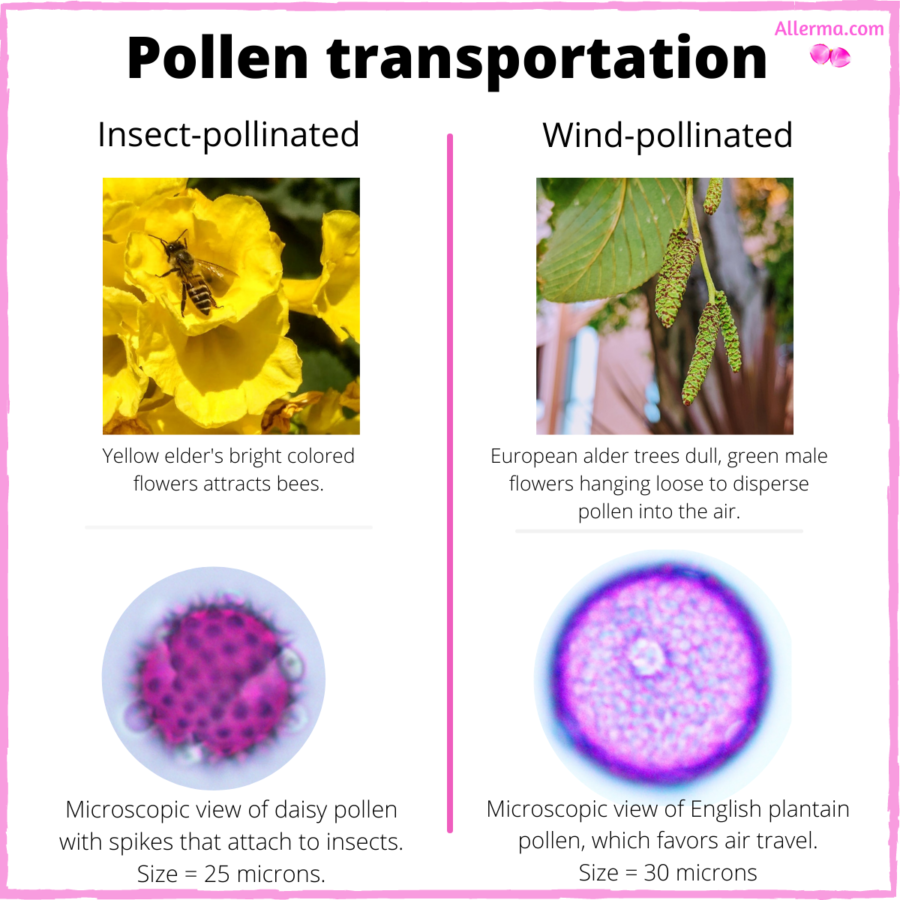

Pollen does not have any mobility or navigation ability of its own. It is entirely at the mercy of insects or wind to carry it to its female counterpart, which could be less than a millimeter away, or, many miles away.

About 80 to 90% of all plant species, use insects to carry their pollen, bees being the most common pollen carrier in this category. The other 10-20% disperse their pollen into the air to use wind as a means of transportation.

Birds, like hummingbirds, and some animals also do act as pollen carriers. For simplicity though, we will just use the two main categorizations of insect-pollinated and wind-pollinated.

1. Insect-pollinated plants generally do not release pollen in the air.

The insect-pollinated plants have evolved to use bright colors or fragrances as a beacon to attract their pollen carriers. Although the end goal of the visiting pollen carrier is to find food or nectar in a plant, it is the bright color or the fragrance of the flowers that attract them to plant in the first place.

The insect transported pollen is sticky and “designed” for clinging to its carrier and not for flight. Therefore, it does not get airborne easily, and hence, human exposure to such pollen is uncommon. As a result, allergies to insect-pollinated plants are rare and limited to people of certain professions that routinely deal with such plants (e.g. a florist)[3]

There are certain plants that are primarily insect-pollinated but occasionally, on dry windy days, lose some of their pollen into the air. Privet, acacia, eucalyptus, and willow are examples of such trees[1]. I am personally allergic to privet and I do my best to avoid the plant during the summer bloom.

So, if you have allergies but like gardening, opt for plants with bright and fragrant flowers.

2. Wind-pollinated plants release copious pollen in the air.

Unlike insect-pollinated plants, wind-pollinated plants are more primitive. They generally have dull, green, or beige flowers, cones, or catkins that do not attract insects. Nor do they offer any nectar to insects or birds. Instead, they rely on wind to carry their pollen to a compatible female stigma.

Some of the oldest species of trees like pines and redwoods are all wind-pollinated [1]. Oak, alder, birch, ash, grass, and ragweed are some other examples of wind-pollinated plants.

Once the plant cast pollen into the air, gravity and wind currents take over its fate. In its random journey, most of the pollen will just become environment dust without ever reaching a female companion. But some pollen, albeit only a small fraction, will land on the stigma of a compatible female to fertilize.

Ordinarily, pollen’s inability to choose its own path would seem like a threat to the plant’s survival. After all, the odds of any single pollen grain randomly landing on a mate are rather slim. But, plants have evolved to mitigate this risk by producing millions or even billions of pollen in just a few weeks. The enormity of the pollen load compensates for its lack of targeted mobility.

Just as an example, a mature alder tree can produce up to 6 billion pollen within the 6 weeks of pollination season[4]. So, if you happen to have an alder tree in your neighborhood, it is almost certain that you will breathe in some of its pollen when it is blooming. Therefore, such wind-pollinated plants that profusely disperse pollen in the air are the likely source of hay fever for most people.

Only male plants release pollen, female plants do not.

All plants are either monoecious or dioecious.

Monoecious, from greek, translates to “one house”, meaning both male and female flowers are on the same plant. Redwood, oak, olive, and grass are all examples of monoecious plants. Since all monoecious plants have male stamens on them, they all produce pollen.

Dioecious translates to “two houses”, meaning male and female flowers blossom on separate trees. In effect, each plant is either a male or, a female. Casuarina, ash, mulberry, and ginkgo are all examples of dioecious trees. Only male dioecious plants have pollen-producing stamens. Therefore, female trees do not produce any pollen and are safe for allergy sufferers.

Almost 80% of wind-pollinated tree species are monoecious, so, the knowledge of tree gender is not that critical overall. But, this information could be useful in determining what trees you grow in your own backyard.

Why does pollen cause allergies?

Allergies are a malfunction of the body’s immune system.

A healthy immune system accurately distinguishes between harmful and harmless particles entering our bodies.

A harmful particle like a virus has two characteristics: It multiplies inside the host and also damages the host’s body. In contrast, a harmless particle, like plant pollen, neither multiplies inside the host nor causes any damage to the body.

When harmful particles enter a body, the immune system mounts a defense to protect it. For example, when we get the common cold from a virus, we experience sneezing, runny nose, fever, etc.

These symptoms are not caused by the virus, but instead are the work of a healthy immune system[3]. This is how our immune system gets rid of the offending germs and makes the body inhospitable for them.

In contrast, when we inhale harmless particles like pollen, the immune system is supposed to ignore them. The pollen should pass through our bodies without any fuss.

However, in a person with allergies, the immune system can no longer accurately distinguish some of the harmless particles like pollen from harmful particles like viruses.

In such a person, instead of ignoring the pollen, the body’s immune system triggers a defense response instead. When the pollen comes in contact with the mucous membrane of the nose, or, eyes, the immune system triggers sneezing, rhinitis, and itching. In more severe reactions, it can also cause inflammation and constriction of breathing airways to keep pollen from entering the body.[3]

The immune system’s reaction to harmless foreign particle is what we call allergies. Such allergies to pollen are also known as hay fever or pollinosis.

It is unusual to be allergic at birth. Most allergic individuals inherit only the capacity to become allergic.

Mary Jelks M.D. in “Allergy plants”

Scientists are still trying to understand why allergies develop only in certain individuals. Most people acquire allergies over time after being exposed to certain allergens. Some acquire allergies during childhood and some as adults.

Various scientific organizations estimate that 10 to 20% of the world population suffers from pollen allergies.

Common hay fever symptoms

A person with pollen allergies may exhibit one or more of these common symptoms :

- Runny nose.

- Sneezing.

- Itching in the eyes, the roof of the mouth, and/or throat.

- Stuffy nose and/or sinus pressure.

- Wheezing and coughing (in case of Asthma).

In contrast to what the name hay fever suggests, a person actually does not get a fever with pollen allergies. Nor does one get body aches or a sore throat like in the case of a cold or flu.

Another key difference between hay fever and cold/flu is that hay fever can persist for several weeks even months. In contrast, a cold or flu resolves itself in a few days.

When is the pollen season for allergy plants?

Most wind-pollinated plants release pollen only for a short few weeks and are inert for the rest of the year. London planetree, for example, spreads pollen for only three to four weeks every year. Casuarina, on the other hand, can disperse pollen for nearly eight weeks.

Although each plant releases pollen only for a few weeks, pollen is present in the air for most of the year. To give some examples, oak, birch, and olive bloom during spring, grass pollen peaks in summer and ragweed spreads misery during fall.

And even though the colder climates are mostly spared from pollen during winter, the temperate climates catch no such break. Texas, for example, is inundated with mountain cedar pollen during winter, while California deals with alder and ash.

All in all, each region could potentially get airborne pollen from 20-30 different allergy plants throughout the year.

We routinely breathe in pollen anywhere from nine to twelve months of the year.

What is cross-reactivity and why does it lengthen the pollen allergy season?

The IgE antibodies are at the front line of our immune systems. They act as triggers that initiate the body’s defense reaction to offending invaders. Such antibodies are found in our noses, skins, lungs, and even our guts.

Theoretically, a set of IgE antibodies should bind with just one type of antigen for which they were formulated. But in the case of a cross-reaction, sometimes they bind with other antigens of similar chemical structure.

In general, such cross-reactivity could be a good thing in fighting disease. For example, antibodies produced in response to a virus could continue to protect the body against some of its mutations through cross-reactivity. However, for an allergy sufferer, this phenomenon only extends the misery endured by the body.

What does this mean for someone with hay fever? Let me explain with the example of my own allergies.

In one of my recent skin-prick tests, I tested positive only for two types of pollen – white alder and olive. Good news, right? After all, being allergic to just two types of pollen is no big deal. Well, not so fast…

I know from experience that I react to all species of alder, birch, ash, olive, and privet in my neighborhood. So, it seems that the antibodies created in response to probably just two types of plants cross-react with the pollen of several other plants.

Alder and birch are both members of the family Betulaceae. It is, therefore, possible that the proteins of their pollen share similar chemical and structural properties. Similar enough to react to the same set of antibodies to trigger allergies.

Olive, ash, and privet, too, all belong to one family Oleaceae. Hence, it is common to find people who are allergic to one, are allergic to all of these plants due to cross-reactivity.

Unfortunately for the allergy sufferer, the plants of the same family do not necessarily bloom at the same time. For example, ash blooms in winter, olive during spring, and privet during summer. Such staggered blooming schedule and cross-reactivity, together, lengthen the allergy season for most people.

The extent of cross-reactivity varies from individual to individual. There are many publications that list the cross-reactivities of pollen and other agents. This is a list of possibilities and by no means is a certainty for everyone[3].

Those with pollen-specific antibodies like tight-fitting gloves will probably have fewer cross-reactions, while those with mitten like antibodies may cross-react with several other pollens.

Dr. Jonathan Brostoff, M.D in Hay – Fever The complete guide

PS: The aforementioned test panel only tested me for alder and olive but not for birch, ash, and privet. After the test, the doctor gave me a cross-reactivity cheat sheet to figure out what else could give me allergies. Since all these trees bloom during different months, over time, I was able to confirm allergies to all of them.

Determining your personal allergy season

In the Bay Area, we see pollen of about 30 different trees, grass, weeds in our year-round air surveys. If you live in the area, you could use this calendar to determine the pollen season for yourself.

For example, I am allergic to alder, birch, ash, and olive. By looking at the calendar, I recognize that I am at risk of getting allergy symptoms from December through June. This implies that I need to avoid pollen and take medicine only for those seven months. For the remaining five months, I do not worry about pollen avoidance or the side effects of the medicine.

With some diligence, you too can determine your own pollen allergy season. Just pay attention to your symptoms and be aware of the plants that are blooming in your neighborhood. Of course, you can use an allergy test to give yourself a head start. But, most commonly performed tests do not predict the actual real-life symptoms well. The only way to be sure is to track symptoms against local pollen counts or calendars.

If you live in the Bay Area, you can check my weekly pollen report to see what is blooming. Or, you could check out the pollen calendar for the entire year. Either way, cross-referencing your symptoms to such reports or calendars could help you figure out your own pollen season.

In other parts of the US, you could check out the pollen counting stations of AAAAI.org. Apart from my own site, this is the only reliable source of the pollen count in the US.

If you do not have access to reliable pollen counts, your best bet is to learn to identify allergy plants. To that extent, I have created detailed guides with photos for most allergy trees. This is a work-in-progress and I will continue to update it over time.

What is the impact of rain on pollen and allergy symptoms?

Rain has a complex relationship with pollen and allergy symptoms. Depending on the conditions, it can aggravate, or, alleviate allergy symptoms.

I have experienced both contrasting effects of rain on my allergy symptoms. On the one hand, I generally breathe easy during and after a heavy downpour, on the other hand, I have also experienced some of the worst allergy symptoms during the first few minutes of rainfall.

I have brought this contradiction to the attention of many scientists that I have met during allergy and aerobiology conferences. And everyone seems to already know that arrival of rain can trigger allergy or asthma symptoms. In fact, this exact phenomenon even has a name – thunderstorm asthma.

Scientists have several theories that explain why the arrival of rain sometimes has an adverse impact on allergy patients. Here’s one such theory from the book Hay Fever by Dr. Jonathan Brostoff [3] that seems to make sense to me.

Theory of why rain sometimes makes allergies worse

Imagine it is the middle of the spring and the environment has a pretty significant pollen load. After a few dry days, the clouds start to gather in the sky and raindrops start to fall. On their journey from the cloud to the ground, raindrops start to collect pollen it encounters.

Initially, it would seem like a good thing that rain is washing off pollen from the air. But, in reality, it is concentrating all the scattered pollen in the air and bringing them to the ground. To make things worse, the pollen absorbs moisture from raindrops and ruptures into even smaller fragments.

When the raindrops loaded with pollen fragments splatter on the ground, the fine allergenic aerosol rebounds back into the air. When inhaled, these finer fragments can travel much deeper into our lungs than pollen. As a result, this aerosol is generally a more potent allergen than the whole pollen.

True, a heavy downpour would eventually wash off these smaller fragments too. But, for the first few minutes of the rain, the air can be fraught with allergenic pollen fragments.

So as you can see, the relationship between rain and pollen is not that straightforward. A light drizzle or the first few minutes of rain during the pollen season can be adverse for allergy patients. On the other hand, a sustained downpour would wash off all allergens to provide some relief until drier conditions return.

What are the best ways to avoid or reduce pollen exposure?

- Learn to identify allergy trees in your neighborhood. During spring, most of the airborne pollen comes from trees and not from grass or weeds. And most of the pollen produced by the tree settles down under it or near it. So, it would make sense for an allergy sufferer to avoid the known allergenic trees while they are in bloom. You can learn to identify allergy trees in our database, which includes photos and fact sheets of common allergy plants.

- Do not park your car or other transportation under a blooming allergy tree. It will collect pollen and give you a concentrated dose when you handle the vehicle.

- During the allergy season, always drive your cars with windows rolled up. All modern cars have internal HEPA cabin filters, which protect you from pollen.

- Limit, or if possible, avoid altogether going out on windy days when a known allergy plant is in bloom.

- During the allergy season, avoid going out when the first rainfall is expected after a dry spell.

- Use a portable indoor HEPA filter air purifier in your home. Once the pollen enters your home, it starts to settle down. A well-positioned air purifier can grab some of the airborne pollen before it has a chance to settle down. To maintain the purifier’s efficiency, clean it on the manufacturer’s recommended schedule.

- Have someone vacuum and wipe clean your home regularly to remove any pollen settled on the surfaces. If you are to do the cleaning yourself, know that it comes with a risk of exposure to pollen. So use a mask and protective goggles while cleaning. Also, use a high-quality HEPA vacuum cleaner, otherwise, it will disperse the pollen back into the air. Similarly, for wiping hard surfaces, use an electrostatic microfiber or disposable Swiffer to make sure dust does not become airborne.

- Launder your bed at least on weekly basis to remove any pollen that has been settling down on it.

- If you return home after spending a considerable time outdoors, change your clothes gently and do not wear them again unless they are washed. Fabrics trap pollen and the act of taking them off or putting them back on can cause exposure.

If you have an allergy to grass, there are some additional pollen avoidance steps that you can take. You can read about them in the grass allergy guide.

Key insights for pollen allergy or hay fever sufferers

- Plants with bright-colored or fragrant flowers are unlikely to cause pollen allergies. Such plants are insect-pollinated and their pollen, in general, does not become airborne.

- The wind-pollinated plants that have dull nectar-less flowers are the primary source of hay fever. Such plants usually release pollen for four to eight weeks and are inert for the rest of the year.

- Some species of the allergenic plants are dioecious, meaning, male and female flowers are on separate trees. For such species, female plants are incapable of producing pollen and can not cause hay fever.

- Cross-reactivity to pollen almost always extends the allergy season for a person. For example, a person allergic to winter blooming ash may also react to spring blooming olive because both plants belong to the Oleaceae family.

- Rain does not always mean the risk of pollen exposure is low. A light drizzle or the first few minutes of rain can actually have an adverse impact on an allergy sufferer.

- Pollen that gets indoors, settles down on surfaces and can become airborne again when disturbed. A HEPA air purifier can help grab some of that pollen before it settles down. Regular cleaning and laundry will ensure settled pollen does not stay in your home for too long.

References

- Pollen Grains by R.P. Wodehouse Ph. D.

- Allergy Plants by Mary Jelks, M.D.

- Hay Fever – Jonathan Brostoff, M.D. and Linda Gamlin

- Sampling and identifying allergenic pollens and molds – By E. Grant Smith